Crisis in South Sudan: Do you know the answers?

Due to a brutal civil war in South Sudan, more than a million people have fled to northern Uganda’s refugee camps. Yet many Americans are unaware of this crisis.

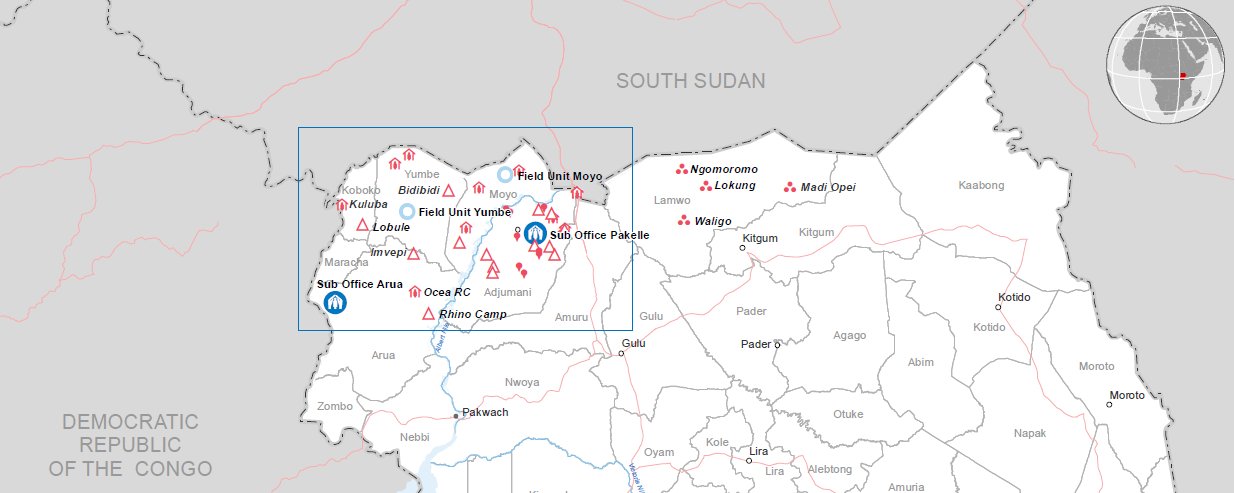

In the map above, you'll see the South Sudanese refugee settlements (represented by red triangles) in the West Nile region of northern Uganda. ChildVoice currently is working in Imvepi Settlement.

Here are 5 relevant Q&As about the South Sudanese refugees and their plight.

Q: How did the South Sudanese refugees get to Uganda?

A: The majority fled on foot as their villages and homes were under attack by rebel troops and government soldiers. Many fled for fear of indiscriminate killings, ethnically motivated attacks, torture, looting, and burning of homes, as well as the forced recruitment of young people by armed groups in South Sudan. Many traveled on foot for several days through the bush, carrying small packs or only the clothes on their backs, the entire time afraid of militant groups and roadblocks on main roads to the border. A very few were evacuated and delivered to the border by bus.

When those on foot reached the Uganda border, they had to find a registration point where they could officially be registered as refugees and then taken by bus to a settlement camp.

Q: What happens to children who arrive alone?

A: Known as unaccompanied minors, these children often were separated from family members as they fled South Sudan. When they arrive at the refugee settlements of northern Uganda, they go through a process of identification and case management.

If a child’s family members cannot be found, a non-governmental organization (NGO) attempts to place them with a South Sudanese foster family. According to World Vision, more than 6,000 unaccompanied minors and separated children have been registered at northern Uganda’s Bidi Bidi Settlement, while more than 3,000 have been registered at Imvepi Settlement.

We’re finding that unaccompanied children sometimes are banding together with other children from their village or community and living together. Such is the case with 17-year-old Susan, who, along with her 18-year-old brother, now takes care of 11 other refugee children at their small hut in the Imvepi refugee settlement. All were separated from their parents when they fled.

Q: Do they have enough food and water?

A: Water security is much better now than it once was, with water deliveries being made to refugee settlements on a regular basis. On the other hand, food insecurity is still high. Currently, Imvepi settlement is not accepting any more people—those already there continue to get a food ration, but they also are being encouraged to do more farming to become more self-sufficient.

OCHA, the UN’s Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, projects that 5.1 million South Sudanese will be food insecure during the first quarter of 2018 (January—March). Many of those people are living in northern Uganda’s refugee settlements.

Q: What are the refugees’ living conditions like?

A: Everyone is trying to create a new, more permanent home in the refugee settlements so they can move forward. People are attempting to make bricks so they can build more permanent structures, replacing the flimsy tarp lean-to’s they’ve been living under with something more weatherproof.

Still, everyday survival is a major challenge as they struggle to provide food for their families and try to earn some sort of meager living.

Q: Do the refugee children go to school?

A: There has been a concerted effort to build more schools both inside and outside the refugee settlements, but unfortunately, resources are limited and the quality of education is low. Schoolrooms are crowded and teachers often have as many as 128 students in class, according to UNHCR, the UN’s official refugee agency.

Children are encouraged to attend school, but the reasons for not attending are many; often, they have to help their families by working in the fields or caring for younger siblings, and adolescent girls with no access to feminine hygiene products are too embarrassed to attend. On top of that, there are safety issues just in getting to and from school, especially for young girls who are victims of rising gender-based violence in the settlements.

According to a recent UNHCR report, 80% of secondary-age South Sudanese refugee children (approx. ages 13 to 17) are not enrolled in secondary education. This is a staggering number.

Q: What is the answer to relieving the suffering of these refugee children?

A: Since 2006, ChildVoice has been restoring the voices of children silenced by war through therapeutic counseling, education, and vocational training, providing them with healing and much-needed hope for a better future.

Over the years, ChildVoice’s Lukome Center in northern Uganda has provided a safe sanctuary community for adolescent girls including former child soldiers and sex slaves, child mothers, orphans, and other highly vulnerable girls. Now, ChildVoice has expanded its services to include war-affected children from South Sudan, particularly those living in the refugee settlements of northern Uganda.

ChildVoice recently began work at Imvepi Settlement after being approved as an official emergency partner with Uganda’s Office of the Prime Minister (OPM). Over the next few months, ChildVoice will form Girl Empowerment Communities that will provide counseling services, psychosocial support, health & hygiene classes (including hygiene packets with basic necessities), vocational training, and agricultural skills. Our goal is to reach more than 2,500 girls who are already child mothers or who are pregnant or at risk of becoming pregnant, providing them with love, hope, and life-changing programs.

Map pictured above by UNHCR. Photos (top to bottom) Andrew Tsang, Kristin Barlow, Neil Mandsager, Nathaniel Ting